By Gowri Somayajula

Right. To recap on where we left off. We had learned about what the geographical boundaries of the EU constituted of, as well as some basic requirements to join the European Union. We haven’t yet looked into the financial operations of this organization, and that’s what this article aims to explore.

We have all heard of the Euro: €, the EU’s adopted currency. But we also must know that not all countries in the EU have chosen to adopt this currency. The Eurozone comprises 19 countries (out of 28) who choose to use the Euro as their national currency. The currency was first introduced in 1995 as a monetary union but physical banknotes didn’t come into circulation until 2002. 343 million people use the Euro, making it the second-largest and second most traded currency after the dollar. Like the United States has the Federal Reserve to monitor trade and to the circulation of currency, the Euro has two banking entities that serve the same purpose:

- The European Central Bank (in Frankfurt):

- The ECB has the sole authority to set and decide monetary policy.

- Its tasks involve setting and implementing monetary policy, taking care of foreign reserves and operating financial market infrastructure.

- While the ECB is governed by European law, it does have shareholders and stock capital, with its €11 billion capital held by the 19 members’ central banks as shareholders.

- The Eurosystem – which consists of all the individual country central banks and the ECB:

- The Eurosystem mints and distributes notes and coins to member countries.

- They conduct foreign exchange operations, as well as holding and managing the official foreign reserves for member states.

The system ensures that capital transfer within EU countries can be counted as domestic transactions rather than international so typical ATM withdrawal fees don’t exist within the EU.

Important happenings:

While the United States faced the 2008 financial crisis, Europe too, dealt with the Eurozone Crisis where several eurozone member states were unable to repay their government debt (these countries were Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Iceland and have the unfortunate acronym of PIIGS). They were also unable to bail out banks within their own national jurisdiction, resorting instead to borrowing money from the IMF and the ECB. It’s hard to say exactly who was at fault here, but economists generally agree that the rapid globalization of markets in the early 2000s followed by lenient lending practices (easy credit) led to the 2008 financial crisis in the United States (or as we know it to be called – the Great Recession). This had a rippling effect across the globe, finally culminating in weeding out poor fiscal policy in European countries. For instance, Ireland (following a period of rapid growth through increased foreign investment) expanded lending in the 2000s, and the sudden ‘08 crisis led the country into recession for the first time since the 1980s.

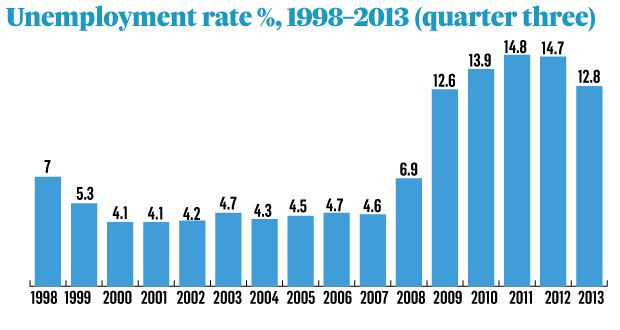

An expansion in the credit line, low corporate tax and interest rates (set by the ECB) as well as poor supervision over the banking industry led to a burst in the Irish property bubble, exposing the market to increased foreign bank borrowings (rising from €15 billion to €110 billion in 4 years). The money was borrowed to fund building projects, and when the real estate bubble burst, the values of these properties plummeted, leaving the banks to be illiquid (a term which means that the assets cannot be sold for cash money that easily) by €4 billion. Businesses closed, immigrants left and the rise in unemployment was catastrophic:

Ireland was saved from bankruptcy with a €67.5 billion bailout loan from the ECB, the IMF and the European Commission and was the first debt-stricken country to repay its loan. In September 2011, all banks were declared financially stable again (and we can see that in the graph above as the unemployment rate fell again in 2013 when Ireland officially exited the bailout). But the effects were devastating. In what was described to be “one of the most expensive banking crises in history”(1), thousands lost jobs, lost money and lost faith. The recovery was long, and slow as Ireland increased its supervision over financial entities. The Financial Regulator resigned. In 2016, for the first time in seven years, net migration was positive as people returned home. Taxes were high while social spending fell (efforts to balance the budget). Foreign companies chose Ireland to start off their European expansion citing its low corporate tax rate of 12.5% (with countries such as Apple, Google and Microsoft booking revenue in Ireland) leading to an increase in foreign investment, and the export rates increased, supported by a weak euro(2). Economists termed the revolutionary turnaround Leprechaun Economics, with Ireland reporting 26% growth in 2016. The other countries didn’t have it so lucky.

PIIGS isn’t just Ireland though and the other stories are much worse (not all of them found the pot at the end of the rainbow if you catch my drift). If the picture I am attempting to paint to you doesn’t scare you if you wonder how bad could it really be, you haven’t seen the effects of a recession. You haven’t seen the harrowing effects of job cuts or wage reductions. I had a friend from Greece who was studying at a summer camp in 2015, seven years after the crisis. Having just received a phone call from her father, she told me that she wouldn’t be able to spend a dime for the remainder of the trip. Not on food, not on transport. “The banks have frozen our accounts,” she had said. There were no tears, I remember. But that was their money, was it not? And it was gone. Just like that.

“Crisis-driven economic insecurity is a driver of populism and political distrust”

“On the Causes of Brexit”, European Journal of Political Economy

You might be wondering what any of this has to do with the UK. The crisis happened to everyone, you say. But that’s where you’re wrong. It’s been theorized that the Eurozone crisis was one of the factors encouraging an already polarized UK to separate from the increasingly interconnected EU financial market, in preparation for another potential crisis. The European Journal of Political Economy published an article in 2018 (titled “On the Causes of Brexit”) stating that the “crisis-driven economic insecurity is a driver of populism and political distrust”(3). Other studies conclude along similar lines: distrust for the stability of an international market has forced the United Kingdom to reconsider its position in the EU. Former British Chancellor of the Exchequer (UK’s National Treasury – I had to look this one up too) Alistair Darling was quoted to have said that “ people’s faith in structures and authority was shaken… A financial crisis became an economic crisis and that the economic crisis became deeply political.”(4) His words echo what research has shown – a rising “them and us” culture. And the UK isn’t alone. We see it here, too in the United States with a large rise in nationalism, closing our borders and markets. It’s rippling through the world, a fear that of the outside, of the unknown. And it’s hurting relationships, severing decades of partnerships and leaving the future a little more unsteady.

I fully accept that all opinions are my own and that I am no expert on these matters. Having said that, I had fun researching and writing this article and I hope to see you here again next time! (Yes these articles will be more regular, I hope).

(1) Patrick Honohan, Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland

(2) Side note for non-econ majors out there a weak currency implies that it becomes expensive to purchase foreign goods. This is because the foreign currency is worth more than the domestic currency. But it also means foreign countries are more willing to buy exports because, in relation to their own currency, the goods exported by the weaker country are cheaper to buy.

(3) Arnorsson, Agust, and Gylfi Zoega. “On the Causes of Brexit.” European Journal of Political Economy, vol. 55, no. December 2018, Dec. 2018, pp. 301–323., doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2018.02.001.

(4) Source