By Gowri Somayajula

It’s 9:30 am Eastern and the trading bell has rung. It sounds a little like a train rattling on its tracks, uncertain where it’s journey will take it. Much like what happened this particular Monday morning. A mere five minutes into trading, the S&P 500 fell by 7% triggering a trading curb (a temporary halt in trading that prevents people from going insane and repeatedly pressing the panic button to sell) that halted markets for 15 minutes. The markets calmed and traded resumed again. Almost as though everything was normal. At the time of writing, the S&P is still down 6.21%. This panic wasn’t caused solely by Coronavirus (it would be unfair to shift the entire blame of the stock market, but rather due to drastic price decreases in the oil prices (the lowest they’ve been since 1991, caused by the beginning of the Gulf War). To quickly summarize what is happening here are a few key bullet points that I won’t go into the details:

- Coronavirus has significantly impacted transportation and export businesses around the world, leading to low demand for oil which led to drastically falling prices.

- OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting consists of 14 oil-producing companies that account for 44% of all oil production and 81.5% of global oil reserves) decided to cut oil production. This was in hopes to prevent oil prices from falling further by cutting supply by 1.5 million barrels a day. Saudi Arabia is the second-largest producer of oil. Russia (not an OPEC member) is the third. Russia and Saudi Arabia as of 2016 worked together on their production quantities. But not this time.

- Russia decided to go against the OPEC decision, choosing to scale production up. Reducing production would benefit American shale producers, and Moscow wanted to retaliate in response to sanctions placed on Russian energy companies. They want to flood the market with their oil (making buying Russian oil cheaper than buying OPEC oil) which would increase the consumption of Russian oil.

- Saudi Arabia reacted in retaliation by also choosing to ramp up production, stating that it would decrease prices for Asian consumers in hopes to increase their global market share.

- The problem: both Russia and Saudi Arabia rely heavily on oil production: Saudi Arabia increasingly so. Petroleum production and sale accounts for 42% of its GDP. Russia’s oil and gas sector only accounts for 16% of its GDP. They both may not be capable of sustaining their economies without diversifying (or seizing the opportunity to gain market share).

- So now we have a 30% price reduction of crude oil prices and since oil is a commodity sold on the stock market, and there are multiple assets linked to the sale of oil, people start selling assets when they face uncertainty. Being unsure means they would rather not take the risk, but instead, sell of toxic assets. And that means the world is going into more panic. While it’s already panicking.

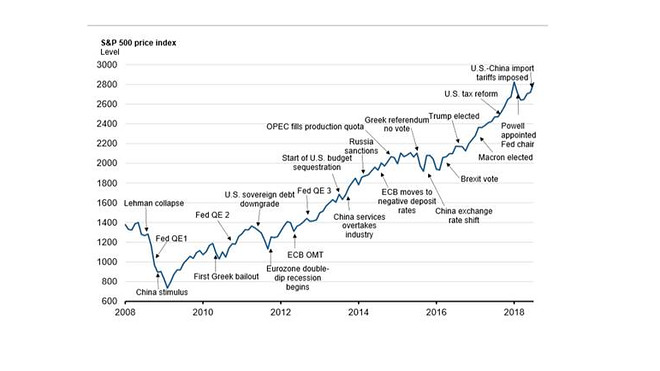

But the general gist of the above was that there was panic. So much of it in fact that the financial markets plummeted so rapidly it triggered a countermeasure that hasn’t been used since the night President Trump won the election. But what can be said about this panic is that we have in fact seen it before. Throughout history, we have had epidemics impact our economies and our stock markets. We’ve had SARS and MERS, we’ve had H1N1, Ebola, and influenza. There was once the bubonic plague. During 2003, the SARS outbreak lasted 7 months, cutting travel back with Asian carriers losing $6 billion and American carriers losing $1 billion. The Brookings Institution conducted a study on the economic impact of closing schools in the United States. ¼th all civilian workers in the US (at the time) had a child under 16. One adult staying home would lose between $5.2 and $23.6 billion in just two weeks. Four weeks could have seen losses of $47.1 billion dollars. But we recovered, did we not? The economy has been a bull market (a market that has seen consistent growth, upward market prices, and faith that these upward market trends will persistent) since 2009.

Look at the above graph. We see the growth, the changes in the global economy that have been made. This current economy is unprecedented. Through globalization, we have the power to trade in an instant, transfer money in seconds and communicate so rapidly that changes across the world have more direct impacts on the economy then has ever been seen before. What we do today has never been done before. Then it will come as no surprise when we will term it this global catastrophe a Black Swan (as described by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his book The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Probable). Any event described as such can be categorized by the following:

- The event occurs as a surprise to the Observer.

- The event has a major effect.

- After it has been recorded, it will be written off as though it should have been predicted, as if the occurrences leading up to the event are observable and in plain sight.

The rise of the Internet was a Black Swan. World War 1 was a Black Swan. The dissolution of the Soviet Union was a Black Swan. And the thing that links them all (no matter how different they appear, is that we will explain it away in the future and eventually the world will continue as usual.

“infectious disease outbreaks such as the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) epidemic of 2002– 04 and the H1N1 (swine flu) epidemic of 2009, behavioral effects are believed to have been responsible for as much as 80 or 90 percent of the total economic impact of the epidemics”

The World Bank Economic, Impact of the 2014 Ebola Epidemic

A study done by the World Bank in 2014 looked into the economic impacts of disease. In the study, they found that “infectious disease outbreaks such as the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) epidemic of 2002– 04 and the H1N1 (swine flu) epidemic of 2009, behavioral effects are believed to have been responsible for as much as 80 or 90 percent of the total economic impact of the epidemics”(1). We attribute most of behavioural economics to things we perceive to be true: things that we perceive will affect us in the future, and that’s what the research reflects: when people panic, it’s not in response to the epidemic itself, but rather a response to the actions taken by individuals, corporations and governments.

Just last week on March 3rd, Jerome Powell (head of the Fed) recently cut the federal interest rate by half a percentage point (0.5%) in response to slowing demand and in hopes of encouraging consumer spending. It wasn’t stated but the underlying message was clear: warning bells are tolling. “It will support accommodative financial conditions and avoid a tightening of financial conditions which can weigh on activity. And it will help boost household and business confidence,” he stated last Tuesday. But interest rates are already low so investors find it impossible to maintain their confidence.

As Captain Jack Sparrow once said in the third Pirates of the Caribbean (At World’s End): “Let us not, dear friends, forget our dear friends the cuttlefish… flipper conories little sausages. Pin them up together and they will devour each other without a second thought. Human nature, in’it? Or… fish nature. So yes! We could hold up here well-provisioned and well-armed and half of us would be dead within the month!”(2). We can’t all expect to be holed up forever (in fact, there isn’t enough toilet paper for us to be holed up forever if Costco shelves are a measure to go by). Humans aren’t predictable, and that’s ok (we would be robots if the models and the theories could accurately contain the entire spectrum of human response and emotion). Worry and concern are natural responses to a pandemic, but it is completely unreasonable for us to expect that things will stay this way forever: be cautious and wary. Dark times are coming. Woe to us all.

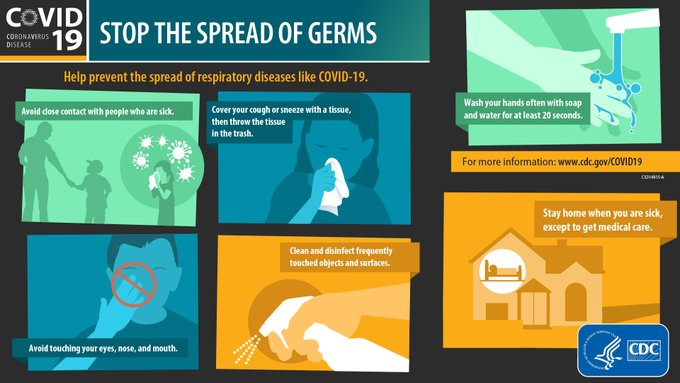

Just kidding. Stay safe, wash your hands for 20 seconds and reduce unnecessary social contact and as Albus Percival Wulfric Brian Dumbledore once said: “Happiness can be found, even in the darkest of times, if one only remembers to turn on the light.”

Citations:

(1) The, World Bank. Economic Impact of the 2014 Ebola Epidemic : Short- and Medium-Term Estimates for West Africa, World Bank Publications, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/berkeley-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1903364. Created from berkeley-ebooks on 2020-03-09 10:37:40

(2) Verbinski, Gore, director. Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End. Walt Disney Pictures, Jerry Bruckheimer Films, 2007.