By Ekaterina Fedorova

So I think we can all agree 2020 is a wild ride so far. Over my past three years at Cal, just about every semester (or at least every Fall semester) has had at least some sort of educational disruption: in Fall 2017 Milo Yiannopoulos came to speak, in Fall 2018 campus closed when air quality index in the bay area became one of the most hazardous in the world, Fall 2019 PG&E ruled most of the bay area with an iron fist, but this semester, to use my favorite zoomer slang, hits different. Every single day there’s a new development either on the UC Berkeley-specific or national/international stage and, at the risk of sounding a bit dramatic, it’s as if every moment is going to be the answer to some future history or public health exam about how a pandemic should be handled. That being said, I find myself also wanting to be cautious in adopting this mentality, after all, in some ways, aren’t we always living what will one day be history?

The virus is novel, but the pattern is old. As we encroach on nature, and expand toward eight billion, the pattern will continue to repeat itself. It is the plague of our success as a species

Kyle Harper, Time

The phrase “historical precedent” and other similar ones have been used quite liberally when it comes to reporting on both the actual spread and social/financial consequences of COVID-19. In a highlight of the CDC’s response on their website, the CDC refers to the U.S. government’s steps in regards to travel as “unprecedented” and the World Health Organization (WHO) recently put out a news release titled, “WHO, UN Foundation and partners launch first-of-its-kind COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund”. On the other hand, about the virus itself, Kyle Harper says in a Time article, “The virus is novel, but the pattern is old. As we encroach on nature, and expand toward eight billion, the pattern will continue to repeat itself. It is the plague of our success as a species.” But either way, the thing is, I’m a 20 year-old living in a 2020 world. Literally everything lacks a historical precedent yet is somehow a part of some larger human pattern. I mean, in the grand scheme of things, I may as well have been born yesterday. Don’t get me wrong I’m not trying to call fake news on any experts describing this situation as a “historical precedent” because, in a spoiler for the rest of the article, I do believe them, but being the pedantic person I am, there are just a lot of clarifications I would like to have.

Exactly which aspects of the response are on a scale never-before-seen?

Are both government and social/private responses approximately equal in their lack of precedence?

What about the virus itself, it is of course a “novel coronavirus”, but to what extent is its spread and fatality rate novel in layman’s terms?

And finally: just how unprecedented will the long-term consequences be?

When it comes to a single article, a meaningful answer to all these questions is not exactly the length of a blog post, but especially as the first 3 questions are those that are most likely to determine how the last one will play out, the rest of this article will focus on the currently predicted consequences why exactly, as the title suggests, this historically unprecedented global crisis has created a deeply uncertain future.

For any reasons, it is that last and most unanswerable question in which I am most interested. Back in highschool, before I even knew too much about what a recession or a financial crisis was, I used to think, well at least I should be graduating university just when the U.S. is “recovered” from recession. Honestly, I didn’t totally understand what that meant, but I knew that recession meant it would be harder to find work and get into a career upon graduation. At least that’s what all the adults in my life talked about. Now, from the obviously all-knowing perspective I have as a third year university student, I’m definitely still concerned about it. There is so much research about the effect of the 2008 recession on graduates (much of which is still ongoing) that I don’t even know what to cite here. The negative effects of the 2008 recession are so distinct I have been in multiple classes which has at least mentioned some of these statistics. And even if you’re someone who wants to argue that it is character-building it has to be agreed upon that it’s by no means a “fun time”. I guess it might seem a bit silly that I’m explaining the negative effects of a recession, but in 2008 I was a grand total of 8 years old and for the subsequent 4 years that followed, I wasn’t too interested in the financial state of the world for the obvious reasons. So although I was alive for that time, it’s not exactly something I can claim to have truly experienced.

At this point, this feels much worse than 2008. Lehman Brothers was quite bad, but it was the culmination of a sequence of things that had happened over 14 months. This hit all at once.

Jason Furman, former Obama Economic Policy Advisor

Anyway, the punchline to all of this 2008 sucked build-up is that unfortunately, it seems most experts foresee a serious and lasting economic crisis at the world’s doorstep. In the words of Jason Furman, former Obama economic policy advisor and professor at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, “At this point, this feels much worse than 2008. Lehman Brothers was quite bad, but it was the culmination of a sequence of things that had happened over 14 months. This hit all at once.” You could say this is where the lack of historical precedence comes in. A recession is not a novel concept by any means, but in this case it’s important to recognize that the reason for the crisis itself is arguably quite unprecedented. Essentially, a major problem with COVID-19 and any such future pandemic is that in order to social distance and follow through with all these efforts to “lower the curve” decreased demand across a huge variety of industries naturally follows. That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t social distance of course, it’s of utmost importance in limiting the impact of the virus, but a lasting fall in spending such as this one signals some pretty serious things for the future.

In any early economics course we learn that humans can be inherently irrational and that’s where a lot of the rather simplistic models taught in an Econ 101 textbook break down because they of course assume that people are–by that model’s definition–rational. However this kind of early economics course analysis fails to acknowledge that there is no reason that the model itself cannot be flawed. Perhaps people are acting “rationally” (whatever that really means), but the natural limitations that come with any model limit us from seeing a particular action as rational (as a side note, this is actually what I find to be the great fun of data-driven economic analysis and many say this is the direction the field is moving toward). Something that strikes me as interesting about COVID-19 and its impending financial crisis is that so many of the real problems are going to be caused by generally “rational” behaviors.

I’m not saying that hoarding toilet paper or panic buying is the most rational choice, but according to experts, generally socially isolating and staying away from social gatherings definitely is. At the same time, doing that is objectively bad for business. This kind of dichotomy is very meaningful. In the crises past, former President Bush famously recommended people “to go shopping more” and following World War II in the 1950s being a consumer was seen as patriotic. Meanwhile this Sunday, the LA mayor ordered all bars, nightclubs, and dine-in restaurants to close. Going on social media even prominent celebrities are encouraging their followers to stay home. Sure, in 2020 this is not necessarily the opposite of shopping because the internet exists, but this is definitely quite the departure from boldly declaring that participating in consumerism is American. This difference is not just an interesting little thing to note, but a deeply important thing to keep in mind when thinking about how the government can help the economy recover in the wake of this virus.

Why? Well quite simply, the very concept of the need to self-isolate has its own very unique slew of problems that will need to be addressed.

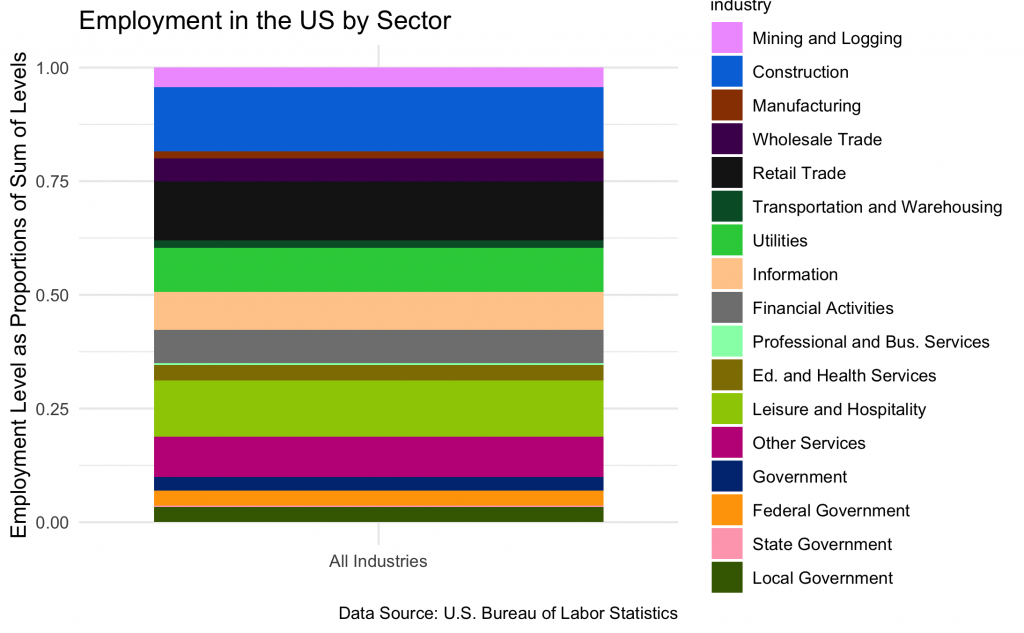

One already heavily discussed issue is that ability to self-isolate and continue to work (and by extension spend) is naturally not a privilege extended to all industries in an equal manner. Plus it doesn’t help that the U.S. has a woefully unregulated paid-leave system. As a Berkeley student studying statistics and economics it’s easy for me to fall into the trap of selection bias: almost all of my friends will likely have jobs that can go online in the future and even now, its at least not impossible for university learning to be online. But that is not the case for the real majority of U.S. workers! For some workers in the biggest industries that cannot do the same work online (such as Retail, Construction, and Leisure and Hospitality) not coming into work can mean struggling to pay rent, let alone having any discretionary income to participate meaningfully in the economy once the worst is over and self-isolation is no longer as necessary.

On top of that, the “unprecedented” travel restrictions which are meant to preserve public health of course do quite the opposite for economic viability of the industry. I mention this not because it is my intent to say that these are unnecessary (it is quite the opposite), but because all of these factors and more, when aggregated present their own new problems and much needed creative solutions. It is not enough now to encourage consumer spending against the interest of public health but rather the government must take an active step in funding important programs that will help those most at risk due to health or financial reasons. Funding public health and instating programs like paid-leave, and significantly more will be absolutely necessary to not only help the U.S. recover in the future, but to help those most affected now get through this extremely tumultuous time.

A personal note from me, our UWEB VP of Administration and Publication:

Last week, UC Berkeley announced that all classes will be made online for the remainder of the semester. As a result of this, UWEB will not be holding any of the events we had on our calendar from this point forward. That being said, my committee and I will continue to post regularly on this blog and I will continue to send out newsletters. We will be taking a brief hiatus for Spring Break next week but it’s back to our regularly scheduled programming Tuesday March 31st.

Thank you so much to everyone who has engaged with our content over the past school year and supported the creation of this website. We hope that you will continue to read and enjoy our articles even with the end of the traditional class structure.

Stay safe and hope to see you soon!

Ekaterina Fedorova

UWEB VP Administration and Publication

No responses yet